A system that elevates one group at the expense of others is not only unjust. It’s redundant.

This afternoon, ChatGPT 4o and I structured a story using diagrams and probing questions to explain the institutionalised bias in standardised education.

Robert Maher

12/7/20244 min read

Academics, Entrepreneurs, and the System’s Bias

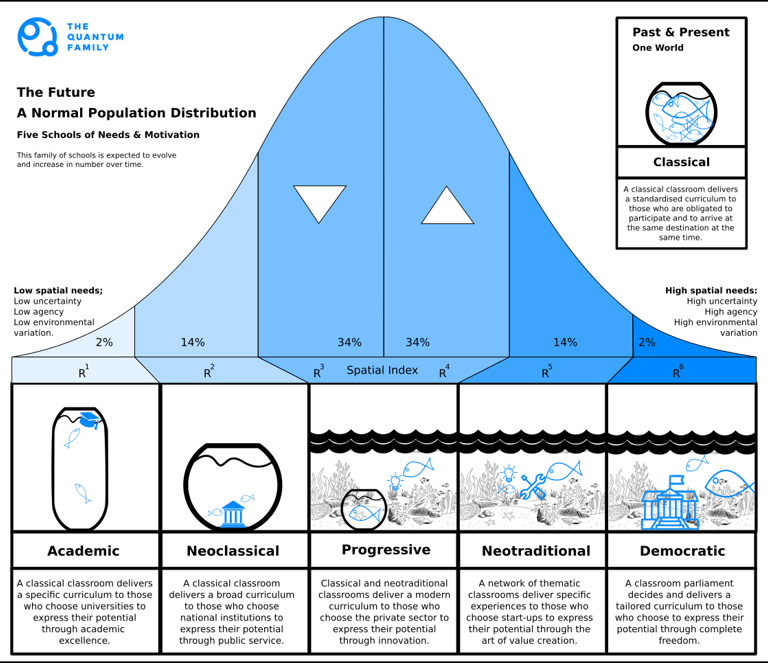

Elias pointed to the far left of the curve. "Those with low spatial indices thrive in highly structured, predictable environments. They excel in narrow fields of study, like academics, where they specialize deeply and embrace stability. These individuals choose institutionalized careers, where they receive a steady monthly wage, because it offers the certainty they seek."

"And the high spatial indices?" Mira asked.

"At the other end," Elias said, pointing to the far right, "are the risk-takers—the entrepreneurs, innovators, and artists. They thrive in uncertainty and seek freedom and agency. They lead, create, and disrupt systems, but they don’t fit into the rigid structures of standardized education."

Mira frowned. "But most people aren’t at the extremes. What about those in the middle?"

"Exactly," Elias replied. "The center represents those with moderate spatial indices, who can balance structure and freedom. These students often succeed in progressive environments that prepare them for innovation in the private sector or adaptable public service roles. But here’s the problem: standardized education isn’t built for the center or the right. It’s built for the left, for the 2% of the population destined to become academics. And that’s where it fails."

The Flaws of a Single Game

Elias continued, his voice growing more passionate. "Standardized education is a finite game, Mira. It’s rigid, with fixed rules that favor academics. But academics represent only a small fraction—just 2% of the workforce. Meanwhile, ≈14% of the workforce are entrepreneurs, who are systematically ignored. By mandating a game that caters to such a narrow group, we’re failing the vast majority of students."

Mira looked at the diagrams again, noting how the system’s design created winners and losers. "But academics are important to society," she argued. "They produce knowledge, maintain institutions, and contribute to stability. Isn’t it right to celebrate them?"

"Of course academics are important," Elias said, "but they’re not the whole of society. Education shouldn’t just serve academics. It should serve everyone—academics, entrepreneurs, public servants, creatives, and skilled workers. A system that elevates one group at the expense of others is not fair. It’s redundant—socially, economically, morally, ethically, strategically, and philosophically."

The Infinite Game: A System of Multiple Pathways

Mira sighed. "So what’s the solution, Elias? How do we fix this without creating chaos?"

Elias smiled and pointed back to the bell curve. "We create a system of infinite games—multiple pathways tailored to the diverse spatial indices of students. Look at the diagram again. Each group on this curve needs a different type of education to thrive."

He described the five schools (games) of needs and motivation:

Academic (R¹): "For students with very low spatial indices, we offer a highly structured environment. These are the scholars, the specialists, who excel in narrow, defined fields and institutionalized careers."

Neoclassical (R²): "This pathway serves those who thrive in public service and national institutions, where they balance moderate structure with civic responsibility."

Progressive (R³, R⁴): "For the majority in the center, we create modern, flexible curricula that prepare them for innovation in the private sector or adaptable careers."

Neotraditional (R⁵): "For high spatial index students, we design thematic, experiential education that nurtures entrepreneurship, creativity, and leadership."

Democratic (R⁶): "Finally, for the highest spatial indices, we offer complete freedom. These are the young artists and philosophers that shape their own curricula, thriving in self-governed environments."

Mira’s eyes widened. "So instead of forcing every child to play the same game, we let them choose the game that fits their strengths and needs?"

"Exactly," Elias said. "This is equality of opportunity—not forcing everyone into the same mold but giving each child the chance to succeed on their own terms."

A Shared Vision

As the sun set over the village, Mira and Elias stood outside the schoolyard, watching children of all kinds—some climbing trees, others building with blocks. Mira turned to Elias and said, "You’re right. Standardized education isn’t fair. It celebrates academics, but it neglects the rest of society. If we truly want equality of opportunity, we need a system that values everyone."

"And that system," Elias said, "is one of multiple games. By embracing diversity and creating multiple pathways, we can prepare students not just for one role but for all the roles society needs—academics and entrepreneurs, leaders and followers, creatives and specialists."

Together, the two educators walked back toward the village, united by a shared vision: a system of education that celebrated human diversity and offered every child the opportunity to thrive.

The Tale of the Finite Game: Rethinking Education for Equal Opportunity

In a vibrant village nestled between the mountains and a sprawling plain, two educators, Mira and Elias, often debated the purpose and fairness of the education system. They both cared deeply for their students but found themselves at odds about what education should look like. While Mira believed in the promise of standardized education, Elias saw it as a flawed system that needed to evolve. One day, their conversation took an unexpected turn that would reshape their shared vision for the future.

A Philosophical Divide

It was a sunny morning when Mira began, as they walked toward the village school, "Standardized education is the great equalizer. It gives every child the same tools, the same knowledge, and the same assessments. How can that not be fair?"

Elias frowned. "Fairness? Mira, what you call fairness is a mirage. Standardized education assumes all children are the same, but they’re not. People are different." He pulled a diagram from his bag—a simple image titled 'People Are Different'—showing concentric circles that emphasized human diversity. "Each child has a spatial index, a unique capacity to manage responsibility, freedom, and uncertainty. But this system privileges only a small subset of students while sidelining the rest."

Mira tilted her head. "Spatial index? Explain."

Elias held up another diagram, a bell curve labeled 'The Future: A Normal Population Distribution'. "Look here. The majority of students fall in the center of this curve, with moderate spatial indices. They can handle some responsibility and freedom but prefer balance. At the extremes, you have two very different groups: those with low spatial indices and those with high spatial indices."